Montjuïc: The Scenic F1 Circuit That Ended in Tragedy

September 4, 2025Nestled on a hill overlooking Barcelona’s vibrant harbor, the Montjuïc circuit was once a jewel in Formula 1’s crown—a breathtaking street track that combined history, beauty, and danger in equal measure. From 1969 to 1975, it hosted the Spanish Grand Prix four times, weaving through iconic landmarks like the Olympic Stadium and the Magic Fountain, its undulating layout a delight for drivers and spectators alike. But beneath its picturesque charm lay a dark undercurrent of safety concerns that culminated in a devastating 1975 tragedy, leading to its permanent exit from the F1 calendar. This tale explores Montjuïc’s rise as a racing venue, the controversies that defined its final race, and the legacy it left behind—a story of glory overshadowed by loss.

A Historic Stage Takes Shape

Montjuïc’s racing roots stretch back to the 1930s, when the wooded parkland atop the hill became a stage for the Penya Rhin Grand Prix. Its strategic location, overlooking Barcelona’s port, had long made it a site of significance, from medieval fortifications to the 1929 International Exposition. That World Fair transformed the hill into a showcase of architecture and innovation, with structures like the grand Olympic Stadium (then known as the Estadi de Montjuïc), the Greek Theatre, and the dazzling Magic Fountain drawing millions. The fair’s legacy provided a panoramic backdrop—sweeping views of the Mediterranean, the city’s bustling harbor, and the distant Tibidabo mountain—that would later enchant F1 crowds.

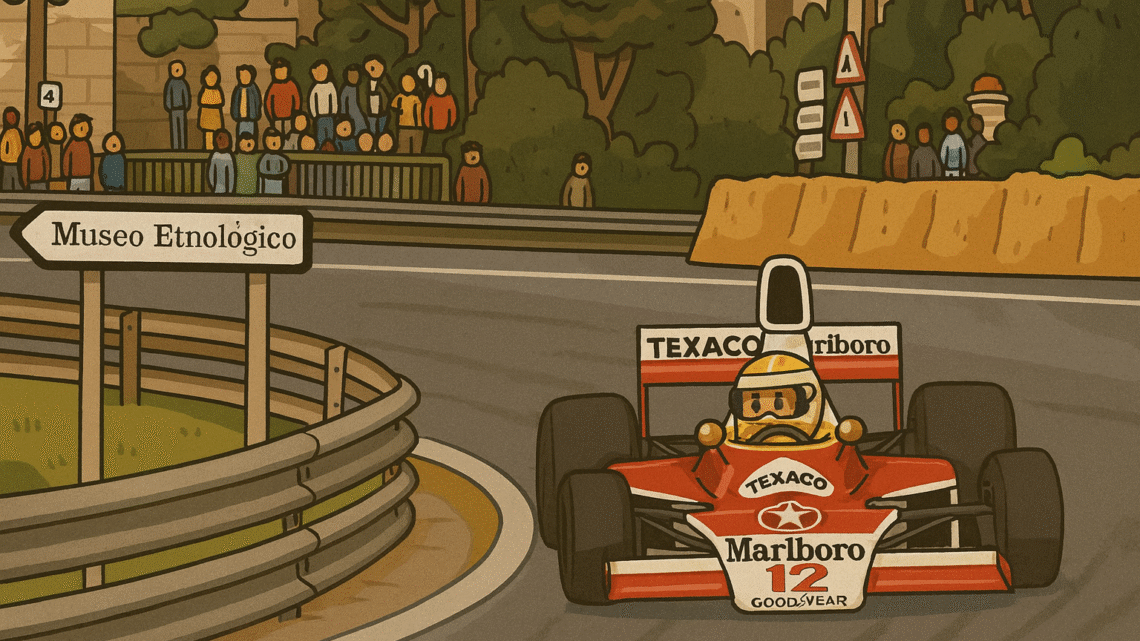

By 1969, with F1 returning to Spain after a hiatus, Montjuïc was chosen to alternate with Jarama, offering a 3.79km anti-clockwise course that blended tight corners, long straights, and elevation changes reminiscent of Monaco. The paddock sat near the old Olympic Stadium, a venue showing its age by the ’70s but still evoking the fair’s grandeur. Cars descended past the Greek Theatre and National Arts Museum, skirted the Magic Fountain’s colorful sprays, and climbed back up the hill—a visual feast that captivated fans with its urban-park fusion. The circuit’s racing history predated F1; pre-war events like the 1933 Spanish GP saw legends like Tazio Nuvolari conquer its twists, building a legacy of speed amid the hill’s historic sites.

The circuit debuted on May 4, 1969, with Jackie Stewart winning in his Matra, beating the field by two laps in a small 14-car grid. Its early races—1971 and 1973—drew praise for the scenery and challenge, with Stewart and Emerson Fittipaldi taking victories. The layout, with its mix of slow and fast sections, tested drivers’ skill, and the panoramic views—Barcelona sprawling below like a postcard—added a unique flavor. But whispers of danger began early—loose barriers and narrow run-offs raised concerns, though the sport’s lax safety standards of the time brushed them aside.

The 1975 Controversy: A Race to Remember for the Wrong Reasons

The 1975 Spanish Grand Prix, held on April 27, marked Montjuïc’s final F1 outing, and it’s remembered not for triumph but for tragedy. The season was already tense, with rising car speeds and inadequate safety measures clashing. Drivers arrived to find the circuit’s Armco barriers in disarray—bolts missing, panels loose, and posts wobbly. Emerson Fittipaldi, a two-time champion, inspected the track and withdrew in protest, a bold stand that highlighted the risks. The rest, pressured by teams and organizers fearing financial loss, reluctantly raced after a rushed overnight fix that fell short.

The race itself was a powder keg. On lap 26, Rolf Stommelen’s Embassy Hill Lola lost its rear wing, likely due to a mechanical failure exacerbated by the poor barriers. The car veered off, crashed into a spectator area, and killed four—two adults and two children—while injuring others. Stommelen, miraculously surviving with severe injuries, was airlifted out as the race halted at half distance. Jochen Mass was declared winner, but only half points were awarded, a hollow victory amid the chaos. Amid the heartbreak, Italian driver Lella Lombardi finished sixth, scoring 0.5 points—the first woman to earn championship points in F1 history, a bittersweet milestone overshadowed by the day’s events.

The fallout was immediate. Drivers, led by Fittipaldi, had warned of the dangers pre-race, but organizers’ negligence—five miles of barrier patched by a skeleton crew—ignited fury. The Grand Prix Drivers’ Association (GPDA) demanded better safety, and F1 abandoned Montjuïc for good. The circuit’s layout, while stunning, couldn’t overcome its inherent risks, a lesson learned too late.

Safety Concerns: A Recurring Theme

Montjuïc’s safety issues weren’t new in 1975. From its inception, the street circuit’s narrow roads and proximity to trees and buildings posed hazards. The 1969 race saw Graham Hill and Jochen Rindt crash due to failing high wings, prompting an immediate ban on them—a precursor to later troubles. By 1973, drivers like Jackie Stewart, a vocal safety advocate, flagged the barriers’ inadequacy, but the sport’s macho culture dismissed such warnings.

The 1975 disaster exposed deeper flaws. Barrier maintenance was haphazard, with loose bolts and missing panels creating deadly gaps. Bales of hay, meant to cushion impacts, were poorly placed or insufficient, failing to absorb the force of high-speed crashes. Run-off areas were minimal, and the elevation changes amplified crash severity. Post-race investigations revealed organizers had prioritized cost over safety, a decision that cost lives. This incident, alongside others like the 1976 German GP at Nürburgring, pushed F1 toward mandatory safety upgrades—better barriers, track inspections, and driver input—changes that reshaped the sport.

The Cultural Impact and Aftermath

Montjuïc’s exit left a void in Barcelona’s racing scene, but its cultural imprint endures. The track’s scenic route through historic sites made it a fan favorite, with crowds packing the hillsides for a view. The 1975 tragedy, however, shifted focus to safety, prompting the city to develop the Circuit de Catalunya for the 1991 Spanish Grand Prix, a purpose-built track that prioritized modern standards.

The accident’s aftermath saw emotional tributes. Stommelen, recovering from a broken leg and pelvis, returned to racing, while Lombardi’s 0.5-point milestone—earned in the race’s truncated chaos—became a quiet point of pride, though overshadowed by grief. Barcelona marked the circuit’s layout in 2004 with plaques, honoring its history while acknowledging its end. Today, the area hosts Olympic venues from 1992, a stark contrast to its racing past.

Montjuïc also influenced F1’s global perception. The tragedy highlighted the need for oversight, leading to the FIA’s stricter regulations. It remains a cautionary tale, discussed in documentaries and fan forums, where its beauty is weighed against its cost.

Legacy: A Beautiful Danger Remembered

Montjuïc’s story is a bittersweet chapter in F1 history. Its four races—1969, 1971, 1973, and 1975—offered some of the sport’s most memorable moments, from Stewart’s dominance to Lombardi’s pioneering points. The circuit’s unique charm, with its parkland setting and urban twists, set it apart, earning it a spot on Autosport’s list of top tracks.

Yet, the 1975 controversy overshadows its glory. The deaths of four spectators and the subsequent ban marked a turning point, forcing F1 to confront its safety failings. Montjuïc’s exit paved the way for safer circuits, but its loss is felt by purists who miss the raw, unpredictable street racing it represented. In Barcelona, the circuit’s ghost lingers in the Olympic Ring, a reminder of a time when beauty and danger danced too close.

As F1 evolves with technology and regulation, Montjuïc stands as a relic of a bolder era—a track where history, spectacle, and tragedy collided. Its story invites reflection: can the thrill of racing justify its risks? For Montjuïc, the answer came too late, leaving behind a legacy as stunning as it is sobering.

Jean-Pierre Van Rossem: The Fraudster Who Brought Ponzi Schemes to F1

James Hunt: The Shunt, the Playboy, and F1’s Ultimate Rockstar

Andrea Moda: The F1 Circus That Crashed and Burned Spectacularly

Prince Bira: The Royal Pioneer

In the annals of Formula 1 history, few figures blend royalty, adventure, and motorsport as…