Cuba Grand Prix: Thrills, Drama, and Revolution in F1 History

February 12, 2026The Cuba Grand Prix captured the world’s attention in the late 1950s. This event blended high-speed racing with political turmoil. Often called Cuba F1, it featured sports cars on Havana’s streets. Juan Manuel Fangio starred as a five-time champion. His kidnapping shocked fans everywhere. A deadly crash added to the chaos. Politics under Batista and Castro shaped its fate. Cancellations followed the revolution. The race’s dismantling marked an era’s end. This post explores its full story.

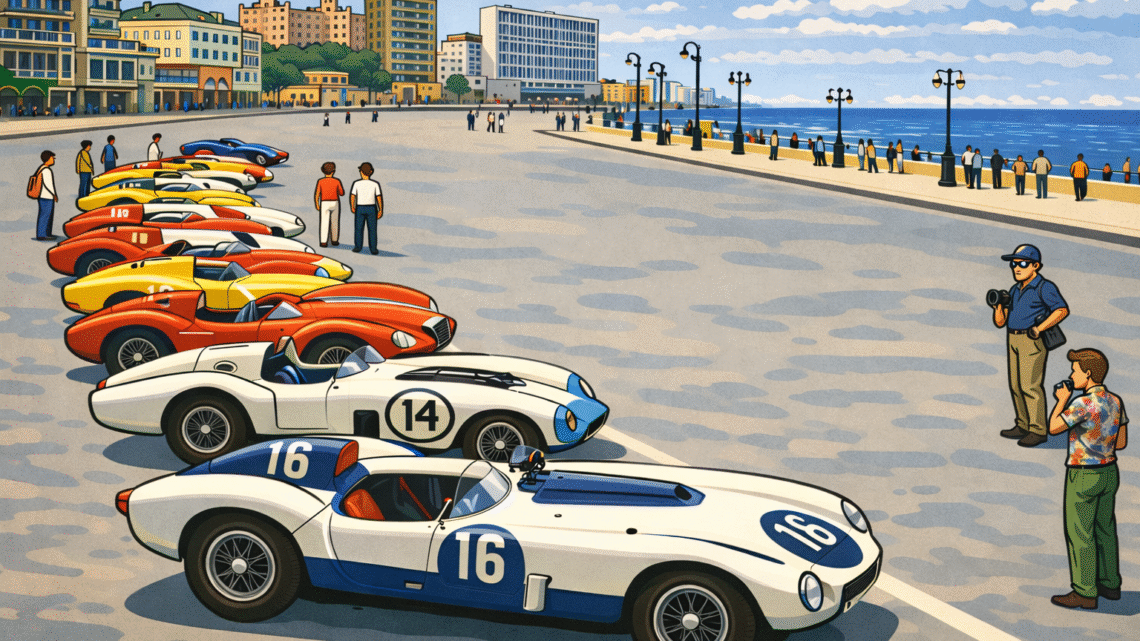

Cuba Grand Prix aimed to boost tourism. Batista’s regime hosted it amid growing unrest. Racing legends like Fangio drew crowds. The Malecón circuit offered scenic views. Engines roared past the sea. Spectators filled the boulevards. Yet, revolution loomed in the background. Castro’s forces challenged the government. The event highlighted Cuba’s glamour and instability. Fans remember it as a unique chapter in motorsport.

Cuba F1 events attracted international stars. They raced powerful Ferraris and Maseratis. The tropical setting added excitement. But safety concerns emerged early. Crowds stood close to the action. Barriers were minimal. Politics intertwined with the sport. Batista used it for propaganda. Rebels saw opportunities to disrupt. The story unfolds with triumphs and tragedies.

This blog dives into the details. We cover the 1957 debut. Fangio’s 1958 kidnapping comes next. The horrific crash follows. Then, the 1960 revival and dismantling. Cancellations and politics explain the end. Legacy reflects on its impact. Cuba Grand Prix remains a tale of speed and revolution.

The First Year: Cuba Grand Prix Debuts in 1957

President Fulgencio Batista launched the Cuba Grand Prix in 1957. He wanted to attract American tourists. Havana’s Malecón became a 3.5-mile street circuit. The track wound along the waterfront. Spectators lined the route eagerly. Over 100,000 people attended. The event promised glamour and excitement. It was part of Batista’s tourism push.

Juan Manuel Fangio headlined the race. The Argentine drove a Maserati 300S. Carroll Shelby competed in a Ferrari 410 Sport. Alfonso de Portago piloted a Ferrari 860 Monza. Other drivers included Stirling Moss. They raced 90 laps, covering 310 miles. The tropical heat tested everyone. Cars reached 150 mph on straights.

Fangio started from pole position. He led early on. Shelby challenged him fiercely. De Portago stayed close behind. The race lasted three hours. Fangio crossed the finish line first. Shelby secured second place. De Portago took third. The podium celebrated international talent.

The event boosted Batista’s image. Tourists flocked to Havana’s casinos. Parties lit up the night. Newspapers praised the success. Yet, unrest simmered in the mountains. Fidel Castro’s 26th of July Movement grew. Rebels plotted against the regime. The Cuba F1 hid these tensions.

Kidnapped in Cuba: F1 legend Fangio’s run-in with revolutionaries – ESPN

Plans for 1958 built on this. Fangio agreed to return. More drivers signed up. Organizers expected bigger crowds. But revolution brewed closer. The event would face unprecedented drama.

Fangio’s Kidnapping: Shocking Twist in 1958 Cuba F1

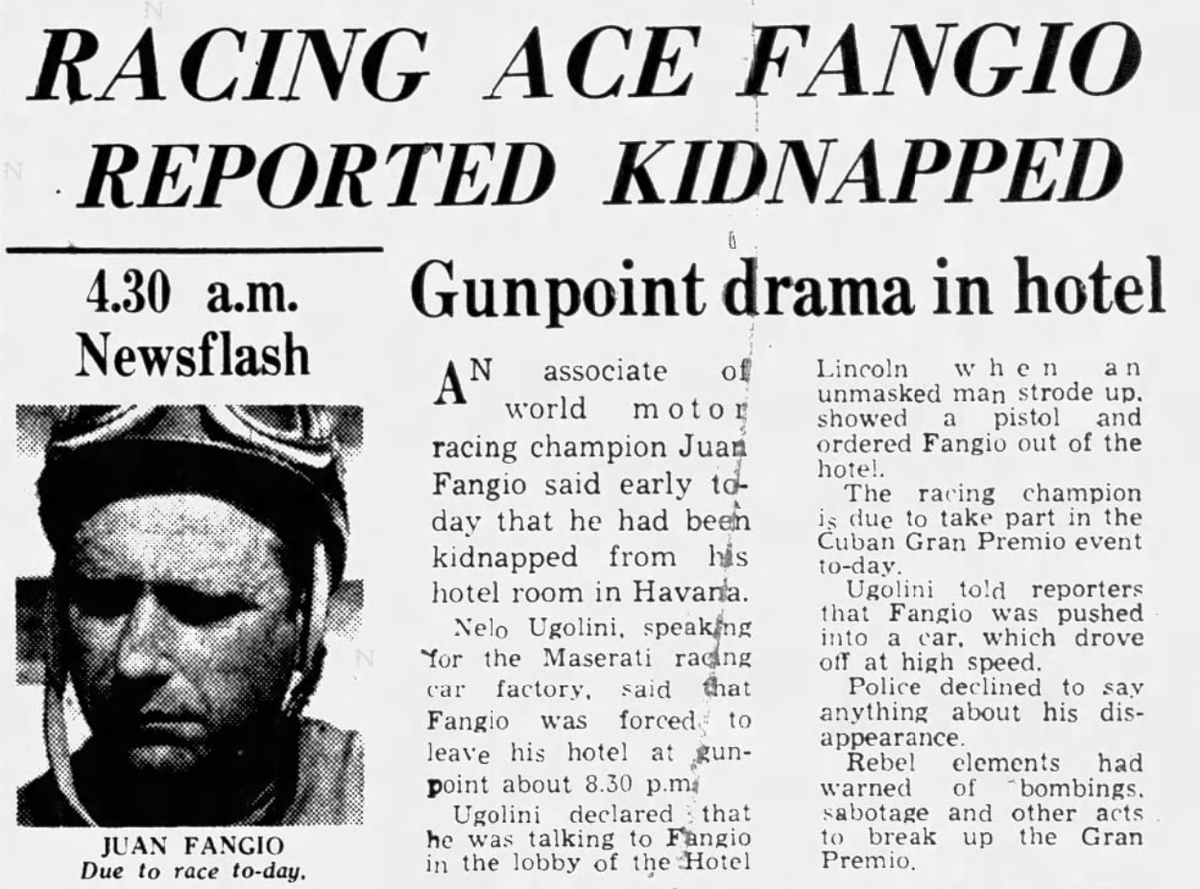

On February 23, 1958, rebels targeted Fangio. He stayed at Hotel Lincoln in Havana. An armed man approached him in the lobby. “You must come with me,” he said. Fangio complied calmly. The kidnapper belonged to the 26th of July Movement. They aimed to sabotage the race. Embarrassing Batista was their goal.

Oscar Lucero and Arnold Rodriguez led the operation. They moved Fangio to safe houses. He chatted with his captors. They discussed racing and life. Fangio played dominoes with them. Captors treated him well. No harm came his way. The stunt sought global attention.

News spread quickly worldwide. Headlines screamed about the kidnapping. Batista’s forces searched frantically. Police checkpoints dotted Havana. Rumors of sabotage swirled. The race proceeded without Fangio. Stirling Moss took the lead role. Tension filled the air.

Fangio stayed captive for 29 hours. Rebels released him after the race. He arrived at the Argentine embassy safe. Fangio held no grudge. He later befriended some kidnappers. The act boosted Castro’s cause. It exposed Cuba’s instability.

The kidnapping overshadowed the event. It highlighted political fractures. More trouble awaited on race day. Fangio’s fame amplified the story. As a five-time champion, he symbolized excellence. Rebels used his status cleverly. Media coverage surged. Newspapers detailed the ordeal. It drew sympathy for the revolution. Batista’s control appeared weak.

The Deadly Crash: Tragedy Hits 1958 Cuba Grand Prix

The 1958 Cuba Grand Prix started February 24. It was a national holiday. Stirling Moss drove a Ferrari 335 S. Masten Gregory joined him upfront. The circuit remained the Malecón. Safety measures stayed basic. Crowds pressed against hay bales. Barriers offered little protection.

On lap six, chaos erupted. Local driver Armando Garcia Cifuentes raced a Ferrari 500 TR. He hit an oil slick from Roberto Mieres’ Porsche. At 110 mph, control vanished. The car slammed into a curb. It flipped into the spectators. Bodies flew through the air. Screams echoed everywhere.

Seven people died, including children. Over 40 suffered injuries. Some lost limbs. The scene horrified witnesses. Rescuers rushed to help. The race halted immediately. Moss was declared winner after six laps. Cifuentes survived with injuries. He never raced again.

Investigations blamed the oil leak. No sabotage was proven. Yet, rumors persisted. The crash exposed street racing dangers. No runoff areas existed. Crowd control failed. Batista faced global criticism. Safety in motorsport came under scrutiny.

The tragedy compounded the kidnapping. Cuba Grand Prix’s reputation suffered. Tourism declined sharply. Rebels gained momentum. Revolution edged closer.

In context, the crash reflected era’s risks. F1 drivers faced similar perils. But Cuba’s politics amplified the fallout. Batista’s regime struggled to respond.

The Last Race: 1960 Cuba F1 and Dismantling

By 1959, revolution triumphed. Batista fled on January 1. Castro’s forces entered Havana. Chaos canceled the 1959 race. The country focused on change. Reforms swept the nation. Racing seemed a luxury.

In 1960, Castro revived the event. He renamed it Gran Premio Libertad. The venue shifted to Camp Columbia airfield. Service roads formed a 3.11-mile circuit. It offered safer conditions. No street hazards remained. The race was part of Havana Speed Week.

Stirling Moss returned triumphantly. He drove a Maserati Tipo 61 “Birdcage.” Pedro Rodriguez raced a Ferrari. Phil Hill competed too. The event ran 65 laps smoothly. Moss won convincingly. Rodriguez took second. Crowds cheered the action. No major incidents occurred.

Yet, politics overshadowed the revival. Castro prioritized social programs. Racing appeared bourgeois. U.S. tensions escalated. The embargo loomed. Investment dried up. The Cuba Grand Prix dismantled quickly. Circuits repurposed for military use.

Photos from 1960 highlight the shift. This Ferrari speeds on the airfield.

The end came swiftly. No races followed in 1961. Bay of Pigs invasion sealed isolation. Motorsport faded in Cuba.

One death marred 1960. Ettore Chimeri crashed fatally. He fell into a ravine. It underscored ongoing dangers. The event’s legacy shifted to history.

Cancellations and Politics: Forces Behind Cuba Grand Prix End

Batista created Cuba Grand Prix for propaganda. His dictatorship faced corruption charges. Rebels fought in the Sierra Maestra. The 1957 race masked these issues. It projected stability. Tourists arrived in droves. But dissent grew stronger.

1958 events accelerated the revolution. The kidnapping embarrassed Batista. The crash killed innocents. Media spotlighted the failures. Tourism plummeted. Castro’s movement gained support. International sympathy tilted their way.

1959 brought Castro’s victory. Batista escaped to exile. Celebrations filled Havana. The race canceled amid transition. New government assessed priorities. Elite sports waited.

1960 attempted normalcy. But socialism clashed with racing. Castro viewed it as capitalist excess. U.S.-Cuba relations soured. The embargo isolated the island. Foreign drivers hesitated. Funding evaporated.

Politics mirrored Cold War divides. U.S. backed Batista initially. Then opposed Castro. Bay of Pigs failed in 1961. Cuba aligned with Soviets. Sports became tools for ideology.

Venues changed forever. Malecón returned to promenades. Airfield turned military. No major races resumed. Minor events appeared decades later.

The politics killed Cuba F1. History views it as collateral damage.

Batista’s fall ended an era. Castro’s rise transformed society. Racing symbolized the old regime. Its dismantling reflected broader changes.

Legacy of Cuba F1: Echoes in Motorsport

Cuba Grand Prix lasted three editions. Yet, its impact endures. It showcased 1950s racing’s raw thrill. Drivers risked everything. Fangio’s kidnapping became legend. Films and books retell the story. The crash spurred safety reforms. F1 evolved with better barriers.

Today, enthusiasts debate its place. Cuba hosts historic car rallies. Minor races nod to the past. But grand events remain absent. Politics still influence sports there.

The tale blends speed with history. Revolution changed Cuba forever. Moss recalled the unique atmosphere. “Nothing compared to it,” he said. Cuba F1 evokes untamed spirit.

In global context, it highlights motorsport’s vulnerabilities. Politics can disrupt any event. The kidnapping inspired security measures. Crashes led to crowd protections. Lessons learned shaped modern F1.

Fans treasure the memories. Vintage photos stir nostalgia. Stories of Fangio’s grace endure. Cuba Grand Prix stands as a cautionary epic.

Its short life left a long shadow. From glamour to chaos, it captivates still.