James Hunt: The Shunt, the Playboy, and F1’s Ultimate Rockstar

September 3, 2025Formula 1 has seen its share of characters, but few burned as bright—or as wildly—as James Hunt. The British driver, born on August 29, 1947, in Belmont, Surrey, wasn’t just a racer; he was a phenomenon, blending blistering speed with a playboy lifestyle that made headlines as often as his victories. Hunt’s 1976 World Championship with McLaren, snatched in dramatic fashion from rival Niki Lauda, cemented his legend, but it’s his off-track antics, raw personality, and fearless exploits that keep fans talking decades later. From vomiting before races to claiming conquests with thousands of women, Hunt lived life at full throttle. This deep dive explores his entry into motorsport, his rollercoaster F1 career, and the stories—on and off the track—that made him an icon. Strap in; it’s a wild ride through the life of “Hunt the Shunt.”

From Suburban Kid to Racing Rebel: Hunt’s Entry into F1

James Simon Wallis Hunt grew up in a middle-class family, with his father a stockbroker and his mother a homemaker. Early on, he showed a rebellious streak, dropping out of school at 18 to pursue racing despite parental disapproval. His first taste of speed came in a Mini, where he honed his aggressive style in club races. By the late 1960s, he progressed to Formula Ford and Formula Three, earning the nickname “Hunt the Shunt” for his spectacular crashes—often due to pushing cars beyond their limits.

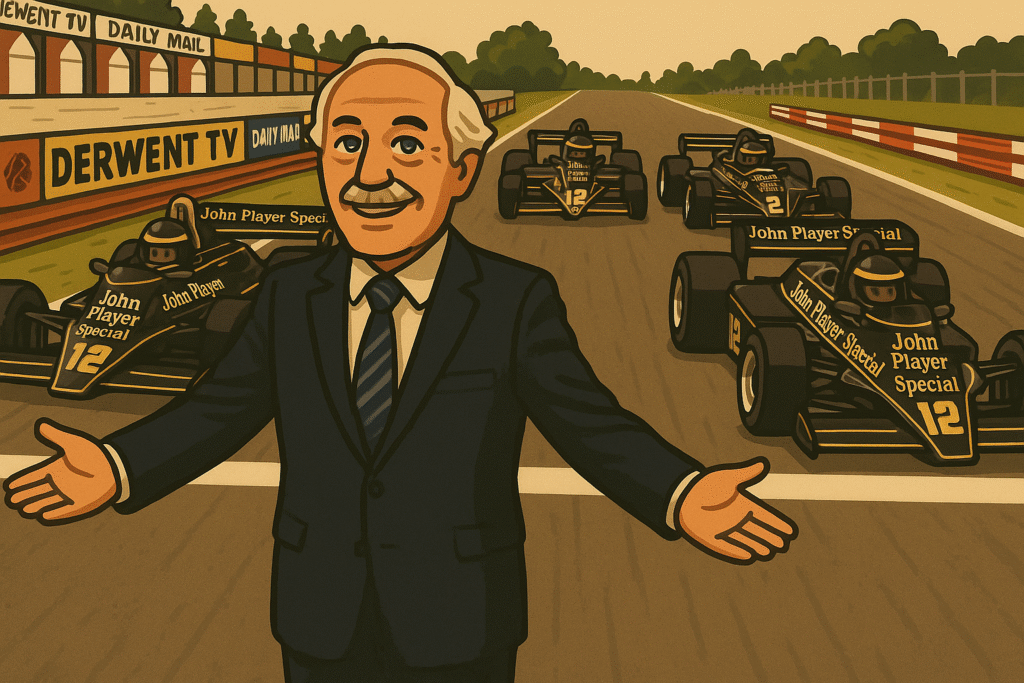

Hunt’s big break came in 1972 when he impressed Lord Alexander Hesketh, a young aristocrat funding a privateer team. Hesketh, charmed by Hunt’s talent and charisma, signed him for Formula Two. Hunt’s raw speed shone, but so did his personality—he once punched rival Dave Morgan after a crash, earning a reprimand but boosting his bad-boy image. In 1973, Hesketh entered F1 with a March 731 chassis, and Hunt made his debut at the Monaco Grand Prix, finishing ninth. His fearless driving quickly paid off: podiums at the Dutch (third) and United States (second) Grands Prix marked him as a rising star. Hesketh’s anti-establishment vibe—parties, yachts, and no sponsors—suited Hunt perfectly, setting the stage for his ascent.

The Hesketh Years: Underdog Glory and Rising Fame

Hunt’s time with Hesketh (1973-1975) was pure underdog magic. In 1973, he scored 14 points, finishing eighth in the championship despite budget constraints. The 1974 season brought the Hesketh 308, a sleek car designed by Harvey Postlethwaite. Hunt won the non-championship BRDC International Trophy at Silverstone and grabbed three podiums (thirds in Sweden, Austria, and USA), netting 15 points for eighth place again. His driving was tail-happy and aggressive, often sliding through corners in a cloud of tire smoke.

1975 was Hesketh’s pinnacle—and Hunt’s breakthrough. The updated 308B chassis delivered his maiden F1 win at the Dutch Grand Prix in Zandvoort. Starting on pole, Hunt held off Niki Lauda’s Ferrari in changing conditions, switching to slicks early and defending inch-perfectly for a 1.06-second victory. Union Jacks waved from the dunes as he crossed the line, a triumph for privateers. He added podiums in Argentina (second), Britain (second), Germany (fourth), and USA (fourth), finishing fourth in the championship with 33 points. Off-track, Hunt’s exploits exploded: he claimed to bed 33 British Airways stewardesses before the 1976 title decider, a tale that fueled his playboy myth.

Hesketh’s financial woes ended the partnership—Lord Hesketh couldn’t fund 1976, so Hunt moved to McLaren, a move that would define his career.

McLaren Mastery: The 1976 Championship Thriller

Joining McLaren in 1976 for a modest $50,000 retainer (plus prize shares), Hunt replaced Emerson Fittipaldi. The M23 chassis, reliable but aging, suited his style. The season became an epic duel with Ferrari’s Niki Lauda, blending speed, drama, and near-tragedy.

Hunt kicked off with a win at the Spanish Grand Prix, but was disqualified post-race for a wide rear wing—reinstated on appeal. He triumphed in France, then won Britain amid controversy: a first-lap crash restarted the race, and Hunt’s victory was protested but upheld. Lauda’s horrific Nürburgring crash in Germany—where he nearly died in flames—shifted the narrative. Hunt won there, then in the Netherlands and Canada, narrowing the gap.

The finale in Japan was cinematic: torrential rain flooded Fuji, Lauda withdrew after two laps citing danger, and Hunt battled to third, clinching the title by one point (69 to 68). Six wins that year, including the USA East, showcased his nerve. Post-race, Hunt partied hard, embodying his “live for the moment” ethos.

1977 brought three more wins (Britain, USA East, Japan) in the M26 chassis, but reliability issues dropped him to fifth with 40 points. His 1978 was dismal—McLaren lagged behind Lotus’s ground-effect cars, yielding just eight points and a 13th-place finish, with one podium in France. Frustrated, Hunt left for Wolf.

The Wolf Stint and Sudden Retirement

Hunt’s 1979 with Walter Wolf Racing was a forgettable swan song. The WR9 chassis was uncompetitive, and he retired from five races with mechanical failures. His best was eighth in South Africa; Monaco’s DNQ was the final straw. On June 8, 1979, Hunt announced retirement at 31, citing lost passion and danger—Ronnie Peterson’s fatal 1978 crash weighed heavily. He finished 13th with eight points, replaced by Keke Rosberg.

Hunt’s F1 stats: 93 entries (92 starts), 10 wins, 23 podiums, 14 poles, 8 fastest laps, 179 points, one championship. His aggressive style thrilled, but crashes and controversies defined him as much as victories.

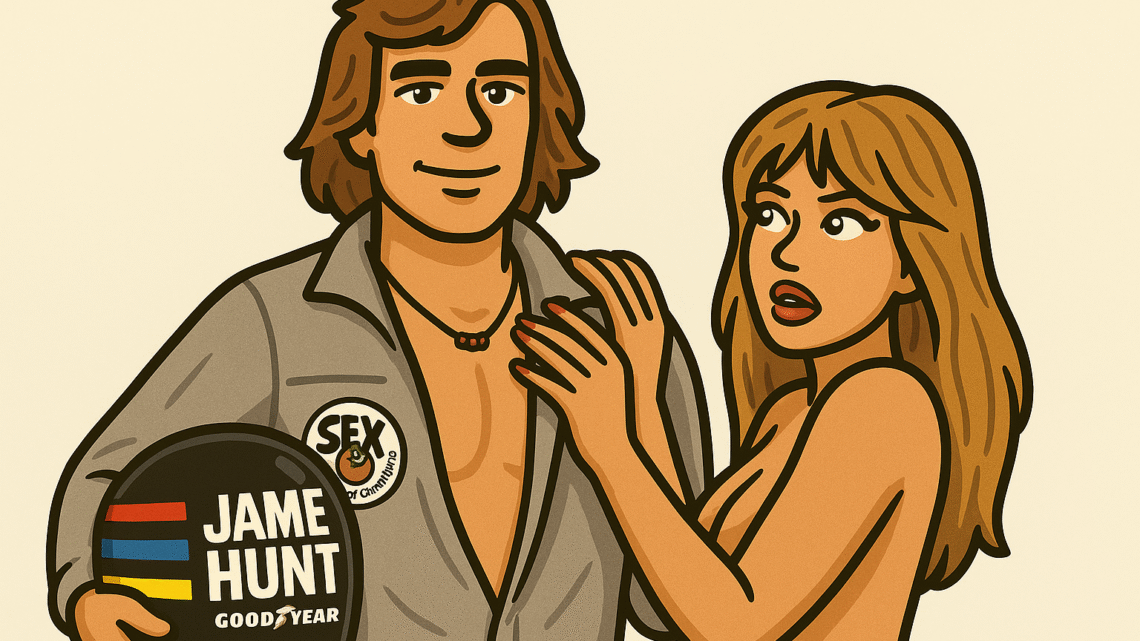

The Playboy Persona: Sex, Parties, and Unfiltered Charm

Hunt’s personality was F1’s perfect storm: charismatic, rebellious, and unapologetically hedonistic. Nicknamed “the Shunt” for early wrecks, he drove with reckless abandon, sliding cars in an era without modern safety. Off-track, he was the ultimate playboy—claiming 5,000 women, including 33 stewardesses before Japan 1976. His driving suit patch read “Sex: The Breakfast of Champions,” later toned down to “Sex” alone.

He reveled in his reputation, boasting in interviews about his conquests and living a life of excess. At parties, he was the center, charming women with his disheveled hair and easy grin. One anecdote: before a 1975 race, he disappeared with a groupie, emerging just in time to qualify on pole. His marriages were stormy—Suzy Miller left for Richard Burton in 1976, reportedly after Hunt’s infidelities; Sarah Lomax divorced him in 1989 amid similar issues, though they had two sons, Tom and Freddie.

Hunt vomited before every race from nerves, yet partied post-victory. At 1976 Japan, he celebrated the title with endless champagne, famously quipping, “I’ve got a world championship to lose!” His rivalry with Lauda was intense but respectful—post-Lauda’s crash, Hunt visited him, and they became friends. Hunt bred budgerigars, banning hunting on his farm, showing a softer side.

Controversies abounded: Heavy drinking, marijuana use, and public brawls. In 1988, he punched a marshal at Paul Ricard for blocking his bike. Broadcasting for BBC from 1980-1993, his candid style shone—calling Jacques Laffite “a mental cripple” or praising rivals unfiltered. Once, mid-race, he lit a cigarette on air, muttering, “This is dull.” His humor was infectious: after a crash, he’d shrug, “Well, that’s racing,” then hit the bar.

Hunt’s womanizing was legendary. He claimed “a girl in every port,” and stories abound of stewardesses, models, and fans. At 1973’s Swedish GP, he romanced a local beauty queen mid-weekend. His 1976 title party allegedly involved multiple partners, a tale he neither confirmed nor denied with a wink. This fun-loving side made him relatable—fans saw a guy living the dream, unfiltered and unafraid.

Off-Track Exploits: Broadcasting, Broadcasting, and Personal Battles

Retirement didn’t slow Hunt. He joined BBC as Murray Walker’s co-commentator, his blunt insights a hit: “The trouble with Ratzenberger is he’s just too slow!” His 1990 Adelaide commentary on Mansell/Senna’s crash is iconic. He wrote books like Against All Odds and consulted for McLaren.

Personal life was turbulent: Divorces, financial woes from bad investments, and battles with depression and alcohol. Friends recalled his generosity—hosting parties at his Wimbledon home—but also isolation. In 1993, at 45, he proposed to girlfriend Helen Dyson, then suffered a fatal heart attack hours later on June 15. No autopsy, but lifestyle factors like smoking and stress were blamed.

Conspiracies swirled—some claimed he faked death to escape debts—but it’s unfounded. His funeral drew F1 stars, with Walker eulogizing his “colorful life.”

Legacy: The Eternal Rebel

Hunt’s impact endures. His 1976 title inspired films like Rush (2013), with Chris Hemsworth capturing his charisma. He popularized F1’s glamour, influencing modern drivers’ personas. Critics note his talent was underutilized—only 10 wins—but his style thrilled.

James Hunt wasn’t perfect—flawed, fearless, fun. From Shunt to champion, his life was a high-speed adventure, reminding us racing’s heart beats in its characters.

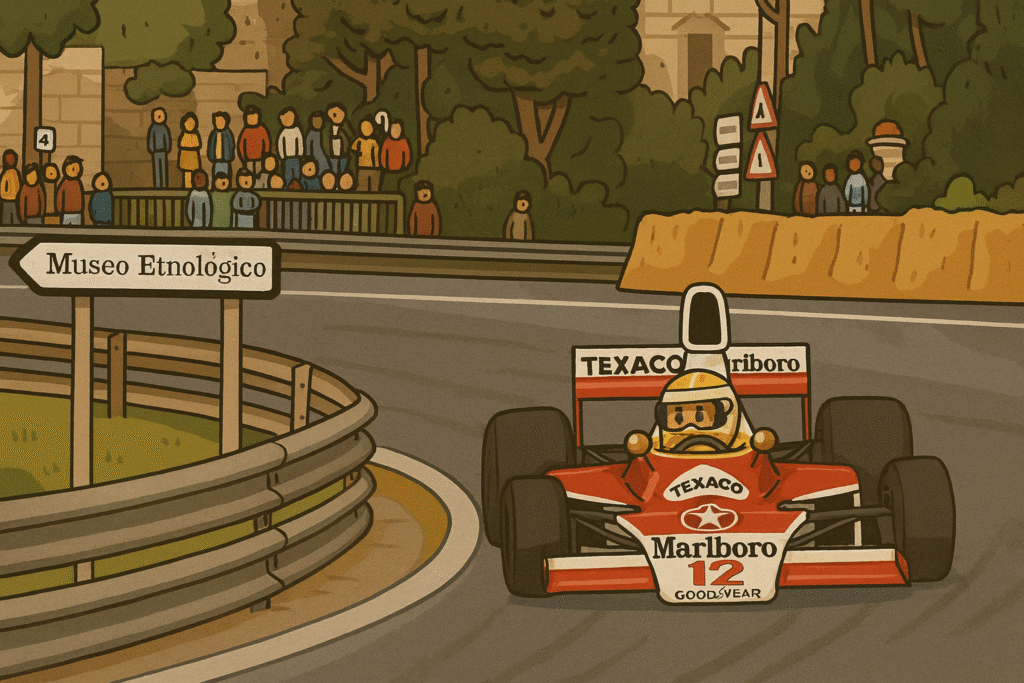

Montjuïc: The Scenic F1 Circuit That Ended in Tragedy

Jean-Pierre Van Rossem: The Fraudster Who Brought Ponzi Schemes to F1

Andrea Moda: The F1 Circus That Crashed and Burned Spectacularly

Prince Bira: The Royal Pioneer

In the annals of Formula 1 history, few figures blend royalty, adventure, and motorsport as…